Secrets de lEgypte ancienne sagesse économies dieu Thoth gnostique mormons rosicruciens francs-maçons

Secrets de lEgypte ancienne sagesse économies dieu Thoth gnostique mormons rosicruciens francs-maçons, Secrets de lEgypte ancienne sagesse dieu Thoth gnostique mormons rosicruciens francs-maçons remise

SKU: 084948

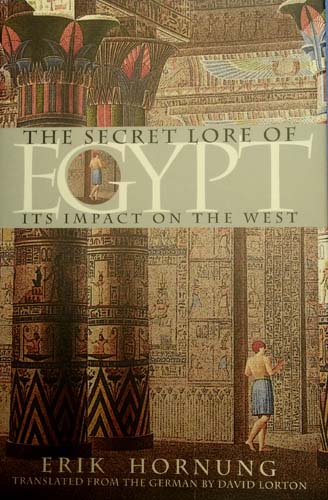

"The Secret Lore of Egypt: Its Impact on the West" by Erik Hornung.

NOTE: We have 75,000 books in our library, almost 10,000 different titles. Odds are we have other copies of this same title in varying conditions, some less expensive, some better condition. We might also have different editions as well (some paperback, some hardcover, oftentimes international editions). If you don’t see what you want, please contact us and ask. We’re happy to send you a summary of the differing conditions and prices we may have for the same title.

DESCRIPTION: Hardcover with dustjacket. Publisher: Cornell University (2002). Pages: 240. Size: 9½ x 6¼ x ¾ inches, 1 pound. Summary: Alchemy, astrology, and other secret sciences have Egyptian roots, and films, popular fiction, and comic books frequently draw upon Egyptian themes. Rosicrucianism, Mormonism, and Afrocentrism all share Egyptian-derived elements. Modern-day esoteric endeavors find an endlessly renewable intellectual reservoir in ancient Egyptian culture, Erik Hornung believes, and are almost inconceivable without Egypt. Although such persistence assures Egyptosophical ideas an extraordinarily widespread impact, the field of Egyptology has largely overlooked this phenomenon.

In "The Secret Lore of Egypt", Hornung traces the influence of the esoteric image of Egypt, especially as it is manifested by the god Thoth, on European intellectual history since antiquity and finds it reasserted even today in the United States. From Gnostic writings and Romantic poetry to Freemasonry and the Theosophist movement, Egyptian deities re-emerge in ever-surprising guises. Since ancient times, Egypt has been associated with esoteric practices and beliefs and regarded as the source of all secret knowledge―an association that, Hornung says, is only loosely connected with historical reality.

CONDITION: NEW. New hardcover w/dustjacket. Cornell University (2002) 240 pages. Unblemished and pristine in every respect. Pages are clean, crisp, unmarked, unmutilated, tightlybound, unambiguously unread. Satisfaction unconditionally guaranteed. In stock, ready to ship. No disappointments, no excuses. PROMPT SHIPPING! HEAVILY PADDED, DAMAGE-FREE PACKAGING! Meticulous and accurate descriptions! Selling rare and out-of-print ancient history books on-line since 1997. We accept returns for any reason within 30 days! #9042a.

PLEASE SEE DESCRIPTIONS AND IMAGES BELOW FOR DETAILED REVIEWS AND FOR PAGES OF PICTURES FROM INSIDE OF BOOK.

PLEASE SEE PUBLISHER, PROFESSIONAL, AND READER REVIEWS BELOW.

PUBLISHER REVIEWS:

REVIEW: Western culture regularly adopts and appropriates themes and motifs from ancient Egyptian art, religious practices, and literature. Hornung here looks at the history of one aspect of this process, the idea of ancient Egypt as the source of esoteric lore and traces the influence of the esoteric image of Egypt on European intellectual history from antiquity to the present, from Gnostic writings and Romantic poetry to Freemasonry and Mormonism, Egyptian deities, monuments, rituals, and ideas re-emerge in new guises.

REVIEW: The study of Egypt as the fount of all wisdom and stronghold of hermetic lore, already strong in antiquity, Hornung (Egyptology, U. of Basel) calls Egyptosophy. Though it was soundly rebuffed by Egyptology, based on conventional science and history, he thinks its continuing impact on western culture.

REVIEW: In this text, Hornung traces the influence of the esoteric image of Egypt on European intellectual history since antiquity and finds it reasserted even today in the United States.

REVIEW: David Lorton, an Egyptologist, is the translator of many books, including Erik Hornungs books “The Secret Lore of Egypt” and “Akhenaten and the Religion of Light”, both from Cornell.

TABLE OF CONTENTS:

1. The Ancient Roots of the "Other" Egypt.

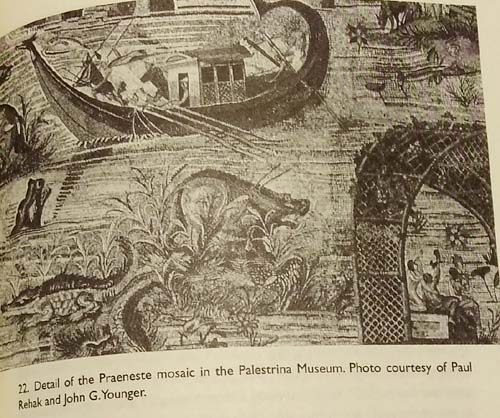

2. Foreign Wonderland on the Nile: The Greek Writers.

3. Power and Influence of the Stars.

4. Alchemy: The Art of Transformation.

5. Gnosis: Creation as Flaw.

6. Hermetism: Thoth as Hermes Trismegistus.

7. Egypt of the Magical Arts.

8. The Spread of Egyptian Cults: Isis and Osiris.

9. Medieval Traditions.

10. The Renaissance of Hermetism and Hieroglyphs.

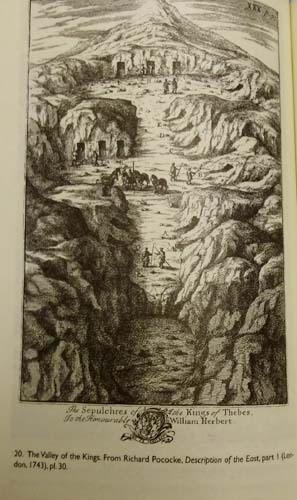

11. Travels to Egypt: Wonder upon Wonder.

12. Triumphs of Erudition: Kircher, Spencer, and Cudworth.

13. "Reformation of the Whole Wide World": The Rosicrucians.

14. The Ideal of a Fraternity: The Freemasons.

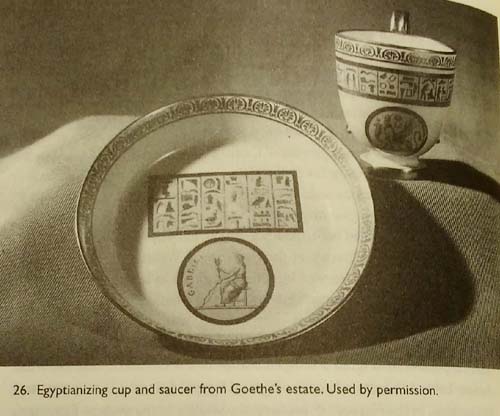

15. Goethe and Romanticism: "Thinking Hieroglyphically".

16. Theosophy and Anthroposophy.

17. Pyramids, Sphinx, Mummies: A Curse on the Pharaohs.

18. Egypt a la Mode: Modern Egyptosophy and Afrocentrism.

19. Outlook: Egypt as Hope and Alternative.

PROFESSIONAL REVIEWS:

REVIEW: The author of four previous Cornell University Press volumes on Egyptology, Hornung (Professor Emeritus, University of Basel) here focuses on "Egyptosophy." This concept is defined as "the study of an imaginary Egypt viewed as the profound source of all esoteric lore. This Egypt is a timeless idea bearing only a loose relationship to the historical reality." Hornung traces the influences of this imaginary Egypt on Western culture from the classical world, through the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, to the present day. He argues that the god Thoth and various Egyptian sages known to the ancient Greeks coalesced into the legendary Hermes Trismegistus, the creator of the art of writing and civilization. Hornung views these mystical and magical "Egyptian" elements as a basis for Gnosticism as well as other secret and metaphysical societies, among them the Rosicrucians, the Freemasons, and the Theosophists. The text presumes extensive knowledge of Western philosophy, art history, and religion; references are made to "the Madonna Platytera" and the "Gnostic Pistis Sophia," for example. Highly recommended for academics, Egyptologists, and those with a special interest in Ancient Egypt and Mythology in general. [Library Journal].

REVIEW: Erik Hornung has rare and perhaps unique advantages for tackling an important and overdue task, namely that of revalorizing the spiritual heritage of Egypt while at the same time describing fairly and rigorously the image of that country in the West...This book is written with vigor and in the authors typically enthusiastic, pellucid style. And how enlivening it is to be reminded that there are colleagues whose learning is broad enough to include familiarity with the Qabalah, the Tabula Smaragdina, and the philosophy of Herder. . . . Congratulations, then, to Professor Hornung for having produced a scholarly, original, and entertaining work, which covers a vast amount of ground with an astonishingly light touch. Those who know the subject of Egyptian survivals will be further enlightened by this volume. [Terence DuQuesne, Discussions in Egyptology].

REVIEW: The study of Egypt as the fount of all wisdom and stronghold of hermetic lore, already strong in antiquity, Hornung (Egyptology, University of Basel) calls Egyptosophy. Though it was soundly rebuffed by Egyptology, based on conventional science and history, he thinks its continuing impact on western culture deserves scholarly attention. He reviews the various occult traditions and their expression during various eras. The original was published by C. H. Becksche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Munich, in 1999, and translated by David Lorton, who has also translated Hornungs earlier books for Cornell. [Book News].

REVIEW: This is an excellent survey for all esotericists and scholars interested in the role of Egypt in the development of western esoteric thought and practice. It is primarily a book about the history of the idea of "ancient esoteric Egypt" as distinct from the actual culture of pharaonic Egypt. Erik Hornung, who is professor emeritus of Egyptology at the University of Basel, Switzerland, and author of such works as "Conceptions of God in Ancient Egypt: The One and the Many and Akhenaten and the Religion of Light", demonstrates the requisite expertise to trace the esoteric idea of Egypt through the labyrinthian history of western European conceptual imagination.

While previous works in the area, specifically Iversens "The Myth of Egypt and Its Hieroglyphs in European Tradition" (1961) and Assmans "Moses the Egyptian: The Memory of Egypt in Western Monotheism" (1997), have addressed various attitudes toward Egypt around specific issues, Hornungs book is a survey of the history of "Egyptosophy" (his term) as conceptualized in various artistic, literary, and esoteric European traditions.

The book is organized chronologically, around the theme of Egyptian wisdom and hermetic lore, ranging from ancient Egyptian roots to classic Greek culture, through chapters on astrology, alchemy, gnosticism, hermeticism, and magic to chapters on the Medieval and Renaissance attitudes toward Egypt, to 17-18th century esoteric movements and fascination with hieroglyphics, to the various Freemason and Rosicrucian recastings, to German Romanticism, Theosophy, and 19th-20th century attitudes, including a look at the problem of Afrocentrism. His goal is to describe "an imaginary Egypt viewed as a profound source of all esoteric lore" -- a Hermetic idea he sees as only tangential to the actual culture and religion of historical Egypt.

Hornung does anchor the Hermetic prespective in the 12th Dynasty (circa 1800 B.C.), at the Temple of Thoth in Hermopolis, in the Book of Two Ways, as a true work of Egyptian wisdom on the afterlife. Thoth, the central figure of Egyptosophy, was a judge, a winged messenger god, scribe of the gods, and guardian of the Eye of Horus whose priests were authors of the famous sacred (esoteric) writings called the "Books of Thoth." By the Ptolemaic period, Thoth had become the primary Egyptian god of magic, incantations, and spells whose name must not be spoken.

It was also in this late period (circa 570 B.C.) that Thoth was transformed by the Egyptian priests under Greek rule into Hermes Trismegistus ("thrice great") and after 240 B.C., a historic religion of Hermes can be traced. Hornung also points out that "esoteric" hieroglyphic language did in fact exist which invested normative hieroglyphic signs with diverse symbolic meanings, creating hieratic priestly codes (for example, the 73 signs for the name of Osiris). At this period also the "Egyptian mysteries" (of Osiris and Isis) were public (not secret) festival reenactments of sacred stories involving death, rebirth and an initiatic vision of the "midnight sun" as shown in many the Egyptian Books of the Netherworld.

However, there are no initiatic texts for Egyptian religion, other than the Hellenistic Isis mysteries; thus, Hornung sees all initiatic ideas about Egypt as Egyptosophic creations based on Greek sources. Assman has described a Hermetic philosophy of a unitary cosmos "of a single god hidden in the multiplicity of things" whose name was secret, arising in Ramessid (New Kingdom) period, thus affirming the possibility of a transmission of an Egyptian "hermetic" philosophy into later Greek and European thinking.

As is well known, many of the famous Greeks attributed the highest degree of wisdom to the Egyptians and it is this praise more than anything else that established Egypt as the primordial source of esotericism. Hermes, as the Greco-Egyptian god, was compared by Diodorus (circa 50 B.C.) to both Moses and Zoroaster, the three forming an esoteric, syncretic triad that would influence both Renaissance and later generations of European esotericists. Writers like Herodotus, Pliny, and Strabo all contributed to a construction of an "Egypt of the imagination" that has lasted to the present.

The Romans regarded Egypt as a lure for exotic, exciting travel and exploration while also holding little receptivity to actual Egyptian religion that was then carried to Rome as a maginalized, poorly understood cult. According to Hornung, its was the Greco-Roman authors that created the myth of "Egyptosophy" as an ideal, imaginary cultural alternative to the dissatisfactions of contemporary Greco-Roman life. Egypt as the "source of all wisdom" and Thoth-Hermes as the "founder of religion" also offered an alternative to the Jewish and Christian worldviews developing in this same period. Egyptian heiroglyphs became a primeval, secret language of Hermes that predated the Biblical story of the Tower of Babel, a theme taken up by Renaissance esotericists with great enthusiasm.

Hornung then discusses Egyptian astrology, alchemy, gnosticism and hermeticism as related to the Greco-Roman period. These are certainly interesting chapters and he makes a number of memorable observations. In Egyptian astrology he notes, there was no belief in the influence of the planets or in their alignments (unlike Mesopotamia); the 36 decans (ten day periods, each with a constellation) were associated with good and bad fates (shai) and with various parts of the body (a Hermetic idea); the zodiac was not adopted until the Ptolemaic period; the earliest know Egyptian horoscope (a Greek concept) is dated to 38 B.C. (compared to 410 B.C. in Mesopotamia) and the oldest is dated 478 A.D.. On Egyptian alchemy, Hornung notes that Zosimos of Panopolis (Akhmim, Egypt) was an Egyptian who united teachings of Hermes with those of Zoroaster and wrote in Greek.

Alchemists like Bolos of Mendes claimed he was instructed in "an Egyptian temple." Yet all early alchemical texts are in Greek while no Egyptian texts on alchemy have been found. Some connection with Egyptian cultic preparation of sacred implements at the temple of Dendara ("House of Gold") under the god Hermes suggests alchemical activity, but only in the Ptolemaic period is there a recognizable Egyptian alchemy. Arab sources also describe alchemy as a "science of the temple" referring to Egypt. However, Arab connections of minerals and salts with planetary influence is strictly non-Egyptian. Hornung points out many tantalizing alchemical parallels with Egyptian texts (including the art of embalming), all deserving careful consideration.

The chapter on Hermeticism is brief but substantive. He discusses the connection between Imhotep and Asclepius as hermetic deities having Egyptian roots in the Middle Kingdom. Clearly, the Corpus Hermeticum (claiming to be the "Books of Thoth"), are primary texts in western esotericism; but they receive only the briefest consideration, being in Hornungs view, primarily Greek creations. The chapter on magic is also brief, focused on the Greek Magical Papyri texts whose origins he attributes to the New Kingdom medical and magical protection texts. He also discusses Egyptian aspects of necromancy, angel magic, Jesus Anubis (who descends to the underworld), and sorcery.

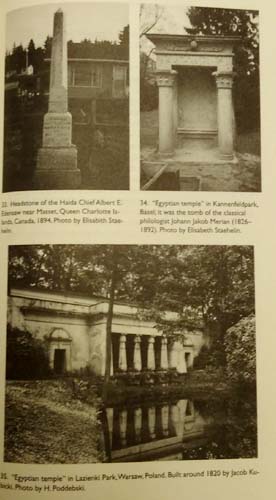

The remainder of the book is primarily historical, a period by period review of the impact of Greco-Roman classical writings on Egypt that provided a basis for European "reimagining" of Egypt as the seat of all wisdom and esoteric traditions. Popularized in the Roman world by the spread of the Isis-Osiris cult, including the worship of Hermes-Anubis, and reinforced by an "oriental exoticism," the architecture and symbolism of Egypt spread over the Mediterranean.

A myth was created that the sacred texts of Thoth were buried (circa 200 A.D.) in the unknown tomb of Alexander the Great, thus "Egyptian wisdom" became a secret, underground lore. With the rise of Christianity, Egyptian lore became anathema and many hermetic-magic texts were burned. In 391 the Christian emperor Theodosius forbid the practice of "all pagan cults" and the Serapium in Alexandria was closed. Slowly the curtain lowers over historical Greco-Egypt and rises on an imaginary, esoteric Egypt that lasts until the present.

During the European Medieval period, Egypt became legendary, a place of refuge for Mary and Joseph, a theme pervasive in Medieval religious art. The Egyptian Coptic Christian church claimed that the Holy Family stayed at the site of one of its most famous monasteries, where Jesus learned Egyptian magic. Augustine discusses Hermes as a wise man and "a master of many arts." The alchemist Albertus Magnus recognized Hermes as the leading authority on astrology. Jewish Kabbalah attributed its symbolism to Jewish esotericism in Alexandria, Egypt and its number symbolism as having Egyptian roots by linking Moses with ancient Egyptosophy.

Hornung also points out Egyptian motifs in the Grail legend, borrowed from alchemy and Isiatic symbols. However, the real impetus to Egyptosophy occurs primarily in the Renaissance and the opening of the Platonic Academy in Florence. Hornung gives a very good overview of the impact "imaginary Egypt" on Ficino and Pico della Mirandola and other Renaissance authors, who all assumed that Greek wisdom originated with the Egyptian priests and the Chaldean (Zoroastrian) magi. Thus the reader is given a tour of the birth of European "hermeticism" through Ficinos translation of the Corpus Hermeticum and through the creation of many hieroglphic books (like Horapollos Heiroglyphika).

This imaginary symbolism is then spread to emblems, architecture, monuments, and other rich secret texts, all linked to "imaginary Egypt." Hornung also reviews the 17th century works of Kircher, Spencer, and Cudsworth as contributing to Egyptosophy (and to the birth of contemproary Egyptology) even though Casaubon and Conring had both attacked and dismissed the Corpus Hermeticum as a fake, claiming that there was no such person as Hermes and the writings of the Corpus were the corrupt creation of a dominating Egyptian priest class (shades of the Protestant revolt!). Nevertheless, Kircher and others invested enormous energy in constructing unique forms of Egyptosophy, attributing esoteric meanings and philosophies to Egypt based on randomly scattered hieroglyphic inscriptions (invented by Hermes according to Kircher), Greek classical writings, and very active imaginations.

Hornung then tracks the Egyptosophy of the Rosicrucians and the Freemasons which mixed the alchemy of Paracelsus with (Egyptian) Kabbalah, Renaissance Hermeticism, and "Egyptian mysteries." Hornung sees the literary traditions of the Rosicrucians as borrowing heavily from the general popularity of esoteric Egyptian motifs then in circulation. Later Rosicrucian societies like the American AMORC founded by Harvey Lewis is heavily dependent on Egyptian symbolism and "esoterica" based in imagined Egyptosophic mystery traditions. Freemasons also track back to the Temple of Jerusalem, esoterically influenced by secret Egyptian building lore.

Masonic tradition is rich in Egyptian motifs and Moses is regarded as a Grand Master of ancient Egypt. Degrees of initiation were modeled on an Egyptosophic ideas concerning the rites of the ancient priest classes. Cagliostro (Giuseppe Balsamo) founded an Egyptian Masonry, the "Rite de la Haute Maçonnerie Egyptienne," in 1784, based, he claimed, on a "secret knowledge learned in the subterranean vaults of the Egyptian pyramids" and from underground priests in the city of Medina. Hornung then goes on to discuss the Egyptian influences in Goethe, Mozart, Herder, and many other German romantic authors and poets.

The closing chapters deal with the Theosophical Society and Anthroposophy. He discusses the pre-Theosophical formation of the 1875 A.D. "Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor" and the Egyptosophic occultism of Helena Blavatsky, showing her creative imagining of Egypt berfore her turn to the east and to occultism Buddhism, granted to her by invisible masters. Rudolph Steiner also borrowed from and recreated an esoteric Egypt under lectures entitled "Agyptische Mythen und Mysterien" drawing on Blavatsky and his own intuitive insights. Steiner claimed that all modern culture is nothing more than a "recollection of ancient Egypt" and that Isis (Maria-Isis) and Osiris are great guiding spirits of our age, particularly the Sophianic Isis.

References to the "wisdom of Hermes" permeate his lectures. Hornung concludes with an overview chapter on the impact and influence of "pyramidology" and mummies (including novels and films) in the 20th century and a summary of recent Afrocentric theories of Egypt which he sees as offering a valuable perspective on ethnicity but one that is from his point of view, extreme and ideological. In closing he discusses briefly Egyptosophy in the works of Herman Hesse, Rainer Marie Rilke, and Thomas Mann. Each chapter has a subject bibliography based on his discussion and referencing primary sources in the area, in itself a valuable reference work, especially for German literature on Egypt and esotericism. [College of Charleston].

REVIEW: Hornung traces Western preoccupation with ancient Egypt as an epitome of the mysterious other, the source of lost or esoteric wisdom, the original font of human knowledge...He concludes with provocative points about the general curricular neglect of Egyptology, yet he also muses on the potential value of a reformed Hermetism in a world crying for reconciliation...Great reading for those with the necessary background. All levels and collections. [Choice].

REVIEW:This book is not a work on Egypt but on images of Egypt in the Western world from Herodotus to Martin Bernal. One could also describe the book as a contribution to the study of western esotericism, a field of research that has begun to flourish of late. The book makes for delightful reading, even though (or, perhaps, because) one cannot be but utterly amazed about the degree of gullibility through the centuries as far as the secret wisdom of ancient Egypt is concerned.

Hornung, himself renowned Egyptologist, deals with sources covering the time-span from the 5th century B.C. to our own day, and he does so in a very competent way. With Herodotus, says Hornung, "there began the construction of a concept of Egypt that has taken on a life and a fascination of its own; it has become ever more unlike pharaonic Egypt, its model, and it has been a part of every esoteric movement down to this day". The book has 19 short chapters of which the first eight deal with antiquity, one with the Middle Ages, and ten with the Renaissance and later periods.

The red thread that runs through all the chapters is the motif of what Hornung felicitously calls Egyptosophy, that is, the mystification of anything Egyptian -- hieroglyphs, pyramids, sphinxes, obelisks, Hermetica -- so as to make all of it into sources of primeval wisdom of divine origin that is to be recovered. Of course, the figure of Thoth-Hermes looms large in much of the material. Hornung sketches the development of Thoth from originally a violent destructor to an exponent of wisdom and knowledge, which in Hellenistic-Roman times results in the figure of Hermes Trismegistos (in Egyptian, thrice great).

This is also the period in which the hieroglyphs are increasingly being regarded not as a regular script but as a system of symbolic signs, intended to conceal rather than to publicize esoteric knowledge, a Greek theory that impeded the decipherment of this script until Champollion (1822). "The fact that they could not be read served only to increase the prestige of the hieroglyphs, for they were believed to embody the secret knowledge ascribed to the Egyptians".

From Diodorus Siculus onward, in later antiquity, the theme that all wisdom sprang originally from Egypt became more and more widespread, not only in Iamblichus De mysteriis Aegyptiorum and Heliodorus Aethiopica. Many authors enrolled ever more of the great thinkers of Greece into the schools of Egypt and even transformed Homer into an Egyptian and the son of Hermes Trismegistus. Of course, there were countervoices, already in antiquity, but on the whole, as Hornung says, "there prevailed a reverence for the evidence of its ancient culture and for the age-old wisdom of its priests, and interest in the mystical Egypt increased from the first century C.E. on".

Aside from the mistaken interpretation of hieroglyphs, Hornung devotes chapters to astrology, alchemy, magic, gnosticism, Hermetism, the spread of the Egyptian cults outside Egypt, etc. When he says that early Christianity was deeply indebted to ancient Egypt, referring to images of afterlife (e.g., a fiery hell), he overlooks that such images had been mediated by Jewish (and Hellenistic) circles and are no proof of Egyptian influence.

The chapters in the second half of the book deal with the renaissance of Hermetism in the late Middle Ages, the impact of travels to Egypt by westerners in the 14th to 16th centuries, the towering figure of Athanasius Kircher (1602-1680), Goethe and Romanticism, the origins and strongly egyptianizing tendencies of the Rosicrucian movement, of Freemasonry, Theosophy (that had its roots in the Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor), Anthroposophy, etc. Hornung also deals with the lonely critical voices of scholars such as Casaubon and Meiners, who were by and large ignored in their time because most people preferred the muddleheaded occultism of Egyptianizers (such as Helena Blavatsky and Rudolf Steiner).

And the end is not yet there. "Hermetic societies that draw on ancient Egypt continue to spring up like daisies" (181). The most amusing chapters are the two on the many varieties of pyramid mysticism in modern times and on the Afrocentric movement revivified by Martin Bernal in his Black Athena, which denies the Greeks all their originality. Here Hornung rightly lends support to the counterattack by scholars such as Mary Lefkowitz.

In spite of his critical attitude towards the occultist egyptianizers, Hornung cannot hide a certain degree of sympathy with some aspects of their enterprise. He therefore ends his book on the following note: "All Hermetism is by its very nature tolerant. Hermes Trismegistus is a god of harmony, of reconciliation and transformation, and he preaches no rigid dogma. He is thus an antidote to the fundamentalism that must be overcome if we desire to live in peace". The book contains many helpful illustrations of an egyptomaniacal nature. On the whole this is a very instructive and charming book that deserves a wide readership. [Pieter W. van der Horst, Ultrecht University. Bryn Mawr Classical Review].

REVIEW: Again Professor Erik Hornung and the Egyptologist-translator David Lorton have teamed with the University Press of Cornell. The first of Ithacas regular Egyptological literature was Hornungs "Conceptions of God in Ancient Egypt", translated by John Baines. It appeared in 1982. The latest book is not directed to professionals but rather to the great number of interested men and women whose orientation may be categorized as esoteric or even spiritual. Prof. Hornung has devoted his life to unraveling many of ancient Egypts religious "mysteries"; and he was a frequent contributor during the 1970s and 1980s to the Eranos conferences held in Ascona, Switzerland.

His focus continues to be the various aspects of Pharaonic religious thought, whether monotheism, the concept of "god", time, aspects of hell, and the like. Within Egyptological circles but also beyond, Hornung has provided us with excellent copies of the New Kingdom religious "books" (e.g., the Amduat and the Litany to the Sun) as well as superb translations and commentaries. Here he begins by deploring the chasm that has come to pass between practicing Egyptologists and religious enthusiasts, whose quarrels he refuses to retrace, as this serves no aim except of a partisan one. Nonetheless, the reader should be forewarned that the author is not a novice seeking the solutions to life through a mystical path of presumed (but false) interpretations of ancient Egypt. His goal is simple and straightforward. It is, in fact, presented in a disarming yet rigorous fashion.

The presentation is basically historical, but each chapter deals with a separate theme. He commences with a healthy appreciation of the problems of humankind in its search for hidden wisdom, denied to all but a select few. Hornung examines "mystical" interpretations one by one, taking a forbearing approach to the myriad false but always interesting notions. It is not his purpose to expose charlatans. He proceeds from the Classical views of Egypt to the popularity of mysticism and Hermes Trimegistus. Out of the Renaissance developed Neo-Platonism and expansive rediscoveries. The Baroque Era in Continental Europe facilitated many a perspicacious and overly clever mind in researching the secret hermetical lore of Egypt.

Famous individuals, it must be admitted, went on these quests: Mozart and the Masons, Dürer, Lessing, Beethoven, Athanasius Kircher, Kepler, Jacques Louis David, and Thomas Mann side by side with Bram Stoker, Krishnamurti, Rudolf Steiner, Aleister Crowley, Joseph Smith, and, to be somewhat ironic, Augustus daughter Julia. I was impressed that Hornung ferreted out the relatively rare and out-of-the-way work by Jurgis Baltrusaitis (La Quête dIsis, Paris, 1967). I had thought that I was the only Egyptologist who was familiar with this volume. Yes, there is a cast of thousands, not even counting the two major Cecil B. De Mille films set in Egypt. Egyptomania commences in the Ptolemaic Era if not earlier, for there is always the amusing Herodotus, a true devourer of gossip, gullible and simplistic.

The Greeks were enamored of Egypt, seeking, as later travelers did, the presumed arcane lore of the Nile. Theosophists and alchemists alike turned their attention to this land, hoping to find in the writings some key to the divine, some gateway to immortality. Egyptologists, Hornung among them, reject these assumptions and presumptions. And like Champollion, Hornung reads the texts. It is doubtful if any of the well meaning pilgrims mentioned in this work could understand the hieroglyphic script. Hence, I found the open-minded and fair approach of the author wonderful in its liberalism and broad in its outlook. If there are criticisms of the various personages Hornung encountered in his time traveling, then I overlooked them. At most, the exclamation marks within parentheses here and there testify to a somewhat amused analysis on his part with regard to these copious productions of the human mind.

But this book may also be read as a history of the fascination all of us cherish. The connection of ancient Egypt to the cultures of the West has never been broken. Whatever misunderstandings, misapprehensions, and crackpot ideas well-meaning laypersons derive from their perceptions of this age-old culture, the attraction, nonetheless, is there; the impetus to self-discovery, however, can lead to erroneous conclusions. Many will find the detailed bibliographies supplementing each chapter to be mines of information. I was struck by the extensive literature that Hornung has read.

The scope of his source material is as far ranging as his subject. Certainly, this work will provide an impetus to future historiographical studies of the concept of Egypt to the outsider. It complements Jan Assmanns recent "Moses the Egyptian" (Harvard University Press, 1997), although the orientation is quite different. I recommend this well-written volume to anyone seriously interested in what Egypt ever meant and presently means to the whole world. As to the veracity of these attempts to scour the Nile Valley for its presumed secrets, it is best to let the writers and mystics speak for themselves. Were their trips worth the effort? That is for others to say. Hornung wisely concludes by noting the rise in new millennialist hopes and fears among us. His tolerant attitude has much to recommend itself. Bigotry is alien to Hermetism. [Anthony Spalinger, University of Auckland].

REVIEW: Hornungs Secret Lore is...enjoyable, dealing with what he calls Egyptosophy, the notion that ancient Egypt is the source of all wisdom and that conventional Egyptology has misunderstood many aspects of this culture. [Antiquity].

READER REVIEWS:

REVIEW: Perhaps responding to the surge in fringe archaeology in Egypt in the 1990s, Hornung gives a whirlwind tour of what he calls "Egyptosophy", the Western tradition of ascribing mystical wisdom to ancient Egypt. Egyptosophy has been one of the core components of the Western esoteric tradition since Roman times, and its led in all sorts of odd directions.

Hornung first covers traditions from the ancient world that drew on Egyptian beliefs or may have done so, including Hermeticism, gnosticism, alchemy, and astrology. A distorted version of ancient Egypt, filtered through and heavily colored by Greco-Roman ideas, made its way through the Middle Ages and became a major fad in the Renaissance. In the 17th and 18th centuries, works of fiction, as well as secret societies like the Freemasons and their offshoots, adopted motifs from this Hellenized version of Egypt to give themselves a mystical, idealistic cachet. Meanwhile, scholars came up with wildly speculative theories about what Egypt was like, based on what little information they had from classical authors.

The deciphering of hieroglyphs in the 19th century opened up the original Egyptian source material, but although new esoteric groups like the Theosophists drew upon the discoveries of Egyptology, they also continued to reuse the Egyptosophical speculation and fantasies of past ages. The mystical cachet of Egypt continues to inspire fiction writers of all kinds and skill levels, while 20th-century esotericism blends Egypt with other sources of inspiration, including Buddhism, kabbalah, Atlantis, and aliens.

Despite many other books which touch on the subject (especially "The Myth of Egypt and Its Hieroglyphs in European Tradition", "The Secret History of Hermes Trismegistus", "Moses the Egyptian", "The Wisdom of Egypt", and "Consuming Ancient Egypt"), there is no other book that gives an overarching picture of how esoteric thought has viewed Egypt through the centuries. Hornungs main purpose may have been to show subjects for future investigation to the academic field of esoteric studies, which was very new at the time he wrote.

REVIEW: "The Secret Lore of Egypt: Its Impact on the West" is on the reccomended reading list for several Egyptian clubs/Egyptological societies. Its a discussion of the various properties of Egyptian mythology, religion and lore; from its effect on art in the ancient world, through its effect on modern-day spirituality. Its an historical look at the various pieces of Egyptian life, and how those pieces have been carried forward to the present time.

The material is separated into chapter according to subsection - art, pottery, spirituality, etc., so you have a sense of what the chapter is about. While its a tough book to follow, I still recommend it, as the material is copious and its the only book which really examines this particular subject. Just be prepared to spend some quality time with this book, as it is dense.

REVIEW: "The Secret Lore of Egypt: Its Impact on the West" is a very informative book. The way in which the rituals are discussed, along with its symbolism, the author certainly did a great job on research and cross-referencing. The bibliography section is golden as well. The first time I read this book, upon thumbing toward the bibliography section I was amazed at the specificity of the titles I was introduced to. I have since read all of those books.

REVIEW: A wonderful work treating the junction of history, science and the occult I found it comprehensive, erudite and lucid, in an absolutely superb translation by David Lorton. Offering respect where this is due and dry humor otherwise, it is a true interdisciplinary text where no one field lords it over another.

REVIEW: Remarkable book. One thing is for sure, the fact that in the West our history starts with the Greeks is a very narrow conception of history and Erik Hornung is doing his best to rectify the situation.

REVIEW: Very interesting. I was really impressed with this book. I enjoy when scholars are able to adequately express how history continues to live in the present, and Hornung did just that.

REVIEW: I love a good read, and this is just that. Nothing is like opening a new book - e-readers eat your heart out! Will be added to my bookcase to be read again and again.

ADDITIONAL BACKGROUND:

REVIEW: Egypt is a country in North Africa, on the Mediterranean Sea, and is home to one of the oldest civilizations on earth. The name Egypt comes from the Greek Aegyptos which was the Greek pronunciation of the Egyptian name Hwt-Ka-Ptah ("Mansion of the Spirit of Ptah"), originally the name of the city of Memphis. Memphis was the first capital of Egypt and a famous religious and trade centre; its high status is attested to by the Greeks alluding to the entire country by that name. To the Egyptians themselves, their country was simply known as Kemet which means Black Land so named for the rich, dark soil along the Nile River where the first settlements began. Later, the country was known as Misr which means country, a name still in use by Egyptians for their nation in the present day.

Egypt thrived for thousands of years (from circa 8000 B.C. to 30 B.C.) as an independent nation whose culture was famous for great cultural advances in every area of human knowledge, from the arts to science to technology and religion. The great monuments which Egypt is still celebrated for reflect the depth and grandeur of Egyptian culture which influenced so many ancient civilizations, among them Greece and Rome. One of the reasons for the enduring popularity of Egyptian culture is its emphasis on the grandeur of the human experience. Their great monuments, tombs, temples, and art work all celebrate life and stand as reminders of what once was and what human beings, at their best, are capable of achieving. Although Egypt in popular culture is often associated with death and mortuary rites, something even in these speaks to people across the ages of what it means to be a human being and the power and purpose of remembrance.

To the Egyptians, life on earth was only one aspect of an eternal journey. The soul was immortal and was only inhabiting a body on this physical plane for a short time. At death, one would meet with judgment in the Hall of Truth and, if justified, would move on to an eternal paradise known as The Field of Reeds which was a mirror image of ones life on earth. Once one had reached paradise one could live peacefully in the company of those one had loved while on earth, including ones pets, in the same neighborhood by the same steam, beneath the very same trees one thought had been lost at death. This eternal life, however, was only available to those who had lived well and in accordance with the will of the gods in the most perfect place conducive to such a goal: the land of Egypt.

Egypt has a long history which goes back far beyond the written word, the stories of the gods, or the monuments which have made the culture famous. Evidence of overgrazing of cattle, on the land which is now the Sahara Desert, has been dated to about 8000 B.C. This evidence, along with artifacts discovered, points to a thriving agricultural civilization in the region at that time. As the land was mostly arid even then, hunter-gathering nomads sought the cool of the water source of the Nile River Valley and began to settle there sometime prior to 6000 B.C.

Organized farming began in the region circa 6000 B.C. and communities known as the Badarian Culture began to flourish alongside the river. Industry developed at about this same time as evidenced by faience workshops discovered at Abydos dating to circa 5500 B.C. The Badarian were followed by the Amratian, the Gerzean, and the Naqada cultures (also known as Naqada I, Naqada II, and Naqada III), all of which contributed significantly to the development of what became Egyptian civilization. The written history of the land begins at some point between 3400 and 3200 B.C. when hieroglyphic script is developed by the Naqada Culture III.

By 3500 B.C. mummification of the dead was in practice at the city of Hierakonpolis and large stone tombs built at Abydos. The city of Xois is recorded as being already ancient by 3100-2181 B.C. as inscribed on the famous Palermo Stone. As in other cultures world-wide, the small agrarian communities became centralized and grew into larger urban centers. Prosperity led to, among other things, an increase in the brewing of beer, more leisure time for sports, and advances in medicine.

The Early Dynastic Period (circa 3150-2613 B.C.) saw the unification of the north and south kingdoms of Egypt under the king Menes ( also known as Meni or Manes) of Upper Egypt who conquered Lower Egypt in circa 3118 B.C. or circa 3150 B.C. This version of the early history comes from the Aegyptica (History of Egypt) by the ancient historian Manetho who lived in the 3rd century B.C. under the Ptolemaic Dynasty (323-30 B.C.). Although his chronology has been disputed by later historians, it is still regularly consulted on dynastic succession and the early history of Egypt.

Manetho’s work is the only source which cites Menes and the conquest and it is now thought that the man referred to by Manetho as `Menes’ was the king Narmer who peacefully united Upper and Lower Egypt under one rule. Identification of Menes with Narmer is far from universally accepted, however, and Menes has been as credibly linked to the king Hor-Aha (circa 3100-3050 B.C.)who succeeded him. An explanation for Menes association with his predecessor and successor is that `Menes is an honorific title meaning "he who endures" and not a personal name and so could have been used to refer to more than one king. The claim that the land was unified by military campaign is also disputed as the famous Narmer Palette, depicting a military victory, is considered by some scholars to be royal propaganda. The country may have first been united peacefully but this seems unlikely.

Geographical designation in Egypt follows the direction of the Nile River and so Upper Egypt is the southern region and Lower Egypt the northern area closer to the Mediterranean Sea. Narmer ruled from the city of Heirakonopolis and then from Memphis and Abydos. Trade increased significantly under the rulers of the Early Dynastic Period and elaborate mastaba tombs, precursors to the later pyramids, developed in ritual burial practices which included increasingly elaborate mummification techniques.

From the Pre-Dynastic Period (circa 6000-3150 B.C.) a belief in the gods defined the Egyptian culture. An early Egyptian creation myth tells of the god Atum who stood in the midst of swirling chaos before the beginning of time and spoke creation into existence. Atum was accompanied by the eternal force of heka (magic), personified in the god Heka and by other spiritual forces which would animate the world. Heka was the primal force which infused the universe and caused all things to operate as they did; it also allowed for the central value of the Egyptian culture: maat, harmony and balance.

All of the gods and all of their responsibilties went back to maat and heka. The sun rose and set as it did and the moon traveled its course across the sky and the seasons came and went in accordance with balance and order which was possible because of these two agencies. Maat was also personified as a deity, the goddess of the ostrich feather, to whom every king promised his full abilities and devotion. The king was associated with the god Horus in life and Osiris in death based upon a myth which became the most popular in Egyptian history.

Osiris and his sister-wife Isis were the original monarchs who governed the world and gave the people the gifts of civilization. Osiris brother, Set, grew jealous of him and murdered him but he was brought back to life by Isis who then bore his son Horus. Osiris was incomplete, however, and so descended to rule the underworld while Horus, once he had matured, avenged his father and defeated Set. This myth illustrated how order triumphed over chaos and would become a persistent motif in mortuary rituals and religious texts and art. There was no period in which the gods did not play an integral role in the daily lives of the Egyptians and this is clearly seen from the earliest times in the countrys history.

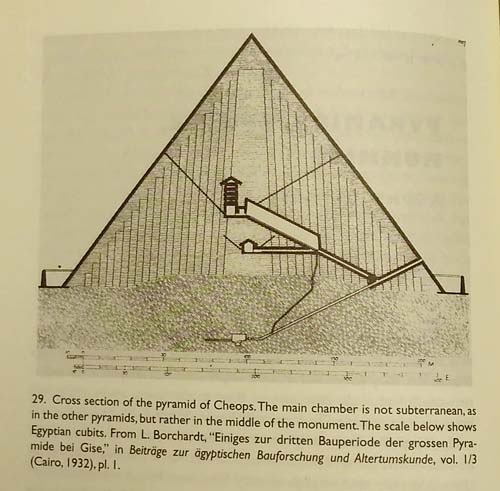

During the period known as the Old Kingdom (circa 2613-2181 B.C.), architecture honoring the gods developed at an increased rate and some of the most famous monuments in Egypt, such as the pyramids and the Great Sphinx at Giza, were constructed. The king Djoser, who reigned circa 2670 B.C., built the first Step Pyramid at Saqqara circa 2670, designed by his chief architect and physician Imhotep (circa 2667-2600 B.C.) who also wrote one of the first medical texts describing the treatment of over 200 different diseases and arguing that the cause of disease could be natural, not the will of the gods. The Great Pyramid of Khufu (last of the seven wonders of the ancient world) was constructed during his reign (2589-2566 B.C.) with the pyramids of Khafre (2558-2532 B.C.) and Menkaure (2532-2503 B.C.) following.

The grandeur of the pyramids on the Giza plateau, as they originally would have appeared, sheathed in gleaming white limestone, is a testament to the power and wealth of the rulers during this period. Many theories abound regarding how these monuments and tombs were constructed but modern architects and scholars are far from agreement on any single one. Considering the technology of the day, some have argued, a monument such as the Great Pyramid of Giza should not exist. Others claim, however, that the existence of such buildings and tombs suggest superior technology which has been lost to time.

There is absolutely no evidence that the monuments of the Giza plateau - or any others in Egypt - were built by slave labor nor is there any evidence to support a historical reading of the biblical Book of Exodus. Most reputable scholars today reject the claim that the pyramids and other monuments were built by slave labor although slaves of different nationalities certainly did exist in Egypt and were employed regularly in the mines. Egyptian monuments were considered public works created for the state and used both skilled and unskilled Egyptian workers in construction, all of whom were paid for their labor. Workers at the Giza site, which was only one of many, were given a ration of beer three times a day and their housing, tools, and even their level of health care have all been clearly established.

The era known as The First Intermediate Period (2181-2040 B.C.) saw a decline in the power of the central government following its collapse. Largely independent districts with their own governors developed throughout Egypt until two great centers emerged: Hierakonpolis in Lower Egypt and Thebes in Upper Egypt. These centers founded their own dynasties which ruled their regions independently and intermittently fought with each other for supreme control until circa 2040 B.C. when the Theban king Mentuhotep II (circa 2061-2010 B.C.) defeated the forces of Hierakonpolis and united Egypt under the rule of Thebes.

The stability provided by Theban rule allowed for the flourishing of what is known as the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 B.C.). The Middle Kingdom is considered Egypt’s `Classical Age’ when art and culture reached great heights and Thebes became the most important and wealthiest city in the country. According to the historians Oakes and Gahlin, “the Twelfth Dynasty kings were strong rulers who established control not only over the whole of Egypt but also over Nubia to the south, where several fortresses were built to protect Egyptian trading interests”. The first standing army was created during the Middle Kingdom by the king Amenemhat I (circa 1991-1962 B.C.) the temple of Karnak was begun under Senruset I (circa 1971-1926 B.C.), and some of the greatest art and literature of the civilization was produced. The 13th Dynasty, however, was weaker than the 12th and distracted by internal problems which allowed for a foriegn people known as the Hyksos to gain power in Lower Egypt around the Nile Delta.

The Hyksos are a mysterious people, most likely from the area of Syria/Palestine, who first appeared in Egypt circa 1800 and settled in the town of Avaris. While the names of the Hyksos kings are Semitic in origin, no definite ethnicity has been established for them. The Hyksos grew in power until they were able to take control of a significant portion of Lower Egypt by circa 1720 B.C., rendering the Theban Dynasty of Upper Egypt almsot a vassal state.

This era is known as The Second Intermediate Period (circa 1782-1570 B.C.). While the Hyksos (whose name simply means `foreign rulers’) were hated by the Egyptians, they introduced a great many improvements to the culture such as the composite bow, the horse, and the chariot along with crop rotation and developments in bronze and ceramic works. At the same time the Hyksos controlled the ports of Lower Egypt, by 1700 B.C. the Kingdom of Kush had risen to the south of Thebes in Nubia and now held that border. The Egyptians mounted a number of campaigns to drive the Hyksos out and subdue the Nubians but all failed until prince Ahmose I of Thebes (circa 1570-1544 B.C.) succeeded and unified the country under Theban rule.

Ahmose I initiated what is known as the period of the New Kingdom (circa 1570- circa 1069 B.C.) which again saw great prosperity in the land under a strong central government. The title of pharaoh for the ruler of Egypt comes from the period of the New Kingdom; earlier monarchs were simply known as kings. Many of the Egyptian sovereigns best known today ruled during this period and the majority of the great structures of antiquity such as the Ramesseum, Abu Simbel, the temples of Karnak and Luxor, and the tombs of the Valley of the Kings and Valley of the Queens were either created or greatly enhanced during this time.

Between 1504-1492 B.C. the pharaoh Tuthmosis I consolidated his power and expanded the boundaries of Egypt to the Euphrates River in the north, Syria and Palestine to the west, and Nubia to the south. His reign was followed by Queen Hatshepsut (1479-1458 B.C.) who greatly expanded trade with other nations, most notably the Land of Punt. Her 22-year reign was one of peace and prosperity for Egypt.

Her successor, Tuthmosis III, carried on her policies (although he tried to eradicate all memory of her as, it is thought, he did not want her to serve as a role model for other women since only males were considered worthy to rule) and, by the time of his death in 1425 B.C., Egypt was a great and powerful nation. The prosperity led to, among other things, an increase in the brewing of beer in many different varieties and more leisure time for sports. Advances in medicine led to improvements in health.

Bathing had long been an important part of the daily Egyptian’s regimen as it was encouraged by their religion and modeled by their clergy. At this time, however, more elaborate baths were produced, presumably more for leisure than simply hygiene. The Kahun Gynecological Papyrus, concerning women’s health and contraceptives, had been written circa 1800 B.C. and, during this period, seems to have been made extensive use of by doctors. Surgery and dentistry were both practiced widely and with great skill, and beer was prescribed by physicians for ease of symptoms of over 200 different maladies.

In 1353 B.C. the pharaoh Amenhotep IV succeeded to the throne and, shortly after, changed his name to Akhenaten (`living spirit of Aten’) to reflect his belief in a single god, Aten. The Egyptians, as noted above, traditionally believed in many gods whose importance influenced every aspect of their daily lives. Among the most popular of these deities were Amun, Osiris, Isis, and Hathor. The cult of Amun, at this time, had grown so wealthy that the priests were almost as powerful as the pharaoh. Akhenaten and his queen, Nefertiti, renounced the traditional religious beliefs and customs of Egypt and instituted a new religion based upon the recognition of one god.

His religious reforms effectively cut the power of the priests of Amun and placed it in his hands. He moved the capital from Thebes to Amarna to further distance his rule from that of his predecessors. This is known as The Amarna Period (1353-1336 B.C.) during which Amarna grew as the capital of the country and polytheistic religious customs were banned. Among his many accomplishments, Akhenaten was the first ruler to decree statuary and a temple in honor of his queen instead of only for himself or the gods and used the money which once went to the temples for public works and parks. The power of the clergy declined sharply as that of the central government grew, which seemed to be Akhenatens goal, but he failed to use his power for the best interest of his people. The Amarna Letters make clear that he was more concerned with his religious reforms than with foreign policy or the needs of the people of Egypt.

His reign was followed by his son, the most recognizable Egyptian ruler in the modern day, Tutankhamun, who reigned from circa 1336-1327 B.C. He was originally named `Tutankhaten’ to reflect the religious beliefs of his father but, upon assuming the throne, changed his name to `Tutankhamun’ to honor the ancient god Amun. He restored the ancient temples, removed all references to his father’s single deity, and returned the capital to Thebes. His reign was cut short by his death and, today, he is most famous for the intact grandeur of his tomb, discovered in 1922 CE, which became an international sensation at the time.

The greatest ruler of the New Kingdom, however, was Ramesses II (also known as Ramesses the Great, 1279-1213 B.C.) who commenced the most elaborate building projects of any Egyptian ruler and who reigned so efficiently that he had the means to do so. Although the famous Battle of Kadesh of 1274 (between Ramesses II of Egypt and Muwatalli II of the Hitties) is today regarded as a draw, Ramesses considered it a great Egyptian victory and celebrated himself as a champion of the people, and finally as a god, in his many public works.

His temple of Abu Simbel (built for his queen Nefertari) depicts the battle of Kadesh and the smaller temple at the site, following Akhenaten’s example, is dedicated to Ramesses favorite queen Nefertari. Under the reign of Ramesses II the first peace treat" alt="Secrets de lEgypte ancienne sagesse économies dieu Thoth gnostique mormons rosicruciens francs-maçons" width="52" height="52" >

Buy now.

Pay later.

Earn rewards

Representative APR: 29.9% (variable)

Credit subject to status. Terms apply.

Missed payments may affect your credit score

FrasersPlus

Available Products

SIMILAR ITEMS

- Secrets de lEgypte ancienne sagesse dieu Thoth gnostique mormons rosicruciens francs-maçons

- Veste de costume blazer cuir Akris noir doublé soie peau dagneau 2 boutons taille 2

- Hot Toys HT MMS665 échelle 1/6 Marvel Morbius figurine jouet modèle

- 4 Litre Prêt à Pulvériser Basislack Neuf or-Orange 2 Métallique Tendance Tuning

- Shinsei Hirano Cinq Montagnes, Rouleau Nuage Tou One Song, Paysage Suspendu, Han

- Pompe DInjection Diesel Pour Audi A4 Berline 03050111 Diesel 2000 (07>10)

- Do You Like Mom Who Attaque Deux fois avec une attaque normale mais un total H6647

- 8 injecteurs de carburant courts Pico Flowmatch TRE 120LB EV6 adaptés à Bosch Siemens

- OPEL MOKKA / MOKKA X Tableau de Bord 1.70 Diesel 96kw 2013 25146688

- Lot de 3 pendentifs porte-clés pendentif manteau sac enfant lingual réfléchissant